One year into the twin COVID-19 and economic crises, 10.1 million Americans remain unemployed and looking for work. That’s well off the highs of April 2020, but nearly twice as many people as in February 2020, right before the health pandemic began to rapidly unfold across the country. Another six million people are working only part-time but would prefer full-time work. Seven million people have dropped out of the labor force because they see no hope of getting a job.

These are distressing numbers. But, as the efforts to contain the virus continue to make progress, WorkingNation is looking to the future as well. Solutions to employment issues are local. Workforce demands differ from community to community. We wanted to know what local leaders and businesses are doing to bring jobs back to their cities and how they are making certain workers and jobseekers have the skills needed to fill those jobs. We found plenty of encouraging steps forward being taken throughout the nation.

Over the next month, we’re sharing them with you in our Focus on… series from Senior Editorial Producer Laura Aka. You’ll see that each city has its own approach, some focusing on a specific industry, some focusing on a particular section of the population. What they all have in common is that they are actionable, proactive efforts to prepare local people for local jobs today and tomorrow. We hope you check back regularly to see what is happening in a community near you and elsewhere around the country.

Ramona Schindelheim, WorkingNation editor-in-chief

Mayor Greg Fischer of Louisville, like other local leaders around the country, is dealing with the aftermath of 2020. His agenda is clear.

Controlling the pandemic is a top priority. “A bad economy is a result of the pandemic. So that’s job one,” stresses Fischer, who also serves as the current president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

What racial equity looks like in America is also part of the conversation, says Fischer.

He adds, “And then workforce. How do we go from these record levels of unemployment we have right now and recreate the economy?”

Moving Into Careers

“Getting the unemployed back to work, in meaningful work that has long-term prospects to it, is going to be an extraordinary challenge. People have to feel dignity in work to feel good about what they’re doing,” says Fischer.

“We don’t want to just train folks to do the same old, same old, we’ve got to move folks into jobs that really represent careers,” stresses Fischer, who says it’s important for residents to have access to training that will support them financially and lead to a good career.

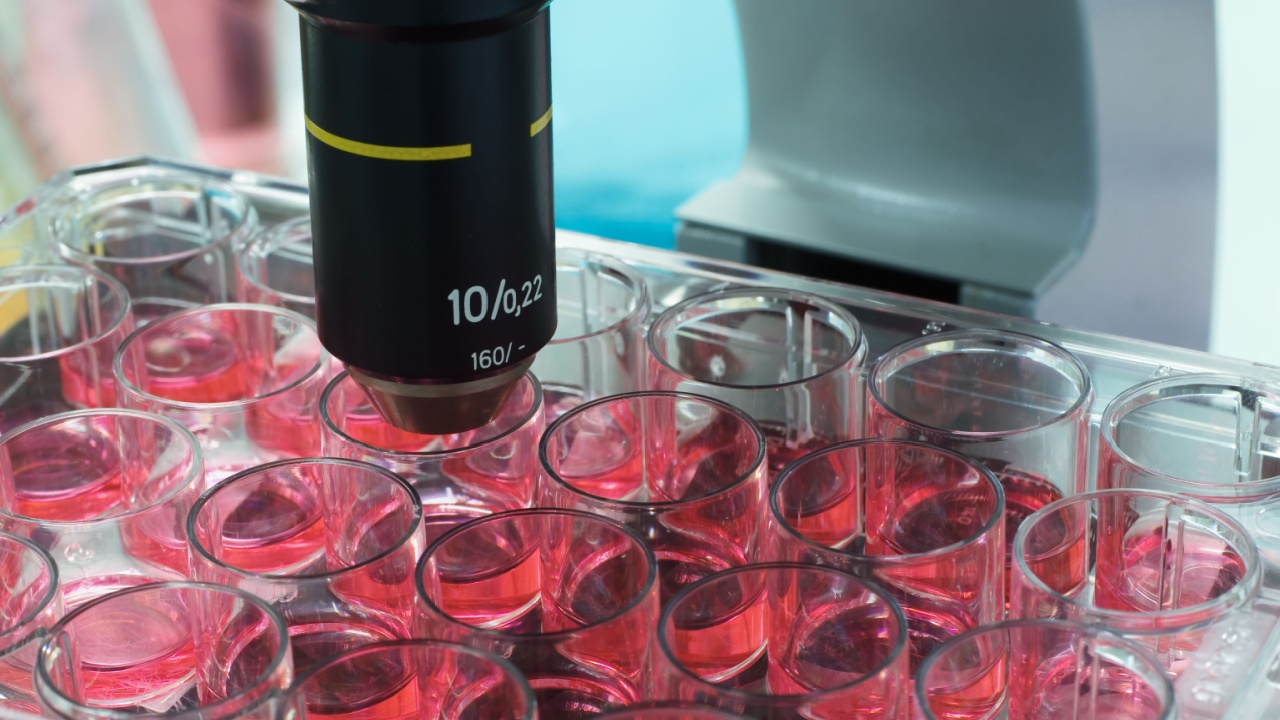

The sectors of wellness and aging care, advanced manufacturing, logistics, and e-commerce are strong in Louisville, according to Fischer. He adds, transitioning people to technology careers is a focus for the city.

KentuckianaWorks is the region’s workforce development board. Its Code Louisville and Tech Louisville are among the current programs that are preparing people for careers in software programming or IT support.

According to the board, there are about 100 unfilled junior software development opportunities open in the greater Louisville area every three months. Code Louisville trains people for those coding jobs through online learning and in-person mentoring.

There’s also an unfilled demand for IT support, with more than 400 job openings posted in the past 90 days. These jobs have a median salary of over $43,000 locally, 20% higher than the median for all occupations. Tech Louisville is offered at no cost to participants and participants earn their Google IT Support Professional Certificate,” according to KentuckianaWorks.

Transforming Public Education for a 21st-Century Workforce

Fischer says collaborations with local businesses are important to ensure there is skilled talent to fill open positions. And, he emphasizes, those efforts start as early as high school in Louisville.

“People can get a taste for what the jobs of the future look like. Then they can develop their education track around that. They can have internships with that, as well, so that there’s already a partnership taking place. It’s meaningful work guided by the future. It’s supported by our education system and our workforce investment board,” he tells WorkingNation.

The Academies of Louisville include 15 high schools in the Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS) district. “There was a real desire to make career and technical education classes more a part of a child’s everyday world,” explains Marty Pollio, Ed.D., superintendent of the JCPS.

Pollio explains the Academies give students access to learning beyond the traditional high school curriculum. “It was about math, English, science, and social studies, and some connections with outside businesses. Looking more towards 21st century jobs and skills.”

In order to give options to students at their respective high schools, each Academy has multiple areas of focus. “We wanted to expand it to have at least four academies in every single school. Some have three, depending on the size of it,” explains Pollio.

“Each school would engage with the district, talk with their school community about the interest, poll their students about the interests that they have, then build an Academy and pathways out of that.”

The range of career exploration is expansive—aviation maintenance, health care, engineering, carpentry, computer programming, veterinary assistant, machinist, financial services, construction, and much more.

Every Academy has an advisory council with members of the business community. Pollio says those partnerships are essential. “We wanted their intelligence, their expertise, their guidance, and eventually their on-the-ground training in their particular area.”

Optimistic About the Future

When Academy students graduate high school, they walk away with far more than a diploma. College credits, industry certifications, work experience, and the mastery of academic and technical skills are just a few ways an Academy education prepares students for life after senior year, according to school officials.

Pollio wants his district’s students to finish high school with options. “We don’t want any student to graduate without that opportunity to go to postsecondary in one way or another. And postsecondary doesn’t just mean four-year colleges.”

“We want every single student to be able to say, ‘I have an employable skill when I graduate, too,’” notes Pollio.

Pollio says all the involved partner are committed to the Academies. “Our business community, our political community, our partners just said, ‘This is what we want in this city. It’s research-based and we’re going to continue to push it.’”

The Need for Federal Support

Michael Gritton, KentuckianaWorks executive director, argues there is overwhelming need for more federal training dollars. “In real terms, the federal investment in workforce is down about 40% from 15 years ago, when you adjust for inflation. So, workforce boards around the country are all starved for resources.”

“Doubling or tripling the funding in order to help people get back to work or get into some of these new jobs is a real, viable strategy for the federal government,” says Gritton.

Looking ahead, Fischer also sounds an optimistic tone about partnership between the country’s cities and the federal government. “I’m a business guy. So if you had a lead product line, cities are the lead product line for America. You should invest in cities. You should encourage cities, and you should lift cities up.”

Laura Aka is the Senior Editorial Producer for WorkingNation.