Last month, more than 3,000 young adults across the country made a year-long commitment to help K-12 students living in areas of concentrated poverty and attending under-resourced schools stay in school, eventually graduate, and prepare for college or a career. In exchange, these mentors themselves will receive help in developing leadership skills through formal training, coaching, and peer learning. They can also earn money that will help pay their own college costs.

These young adults are part of City Year, a national nonprofit program founded in Boston in 1988 that is now in more than 350 schools in 29 U.S. cities. Ten million students live in communities of concentrated poverty and they are “twice as likely to face traumatic experiences that interfere with their ability to arrive at school every day ready to learn,” according to City Year.

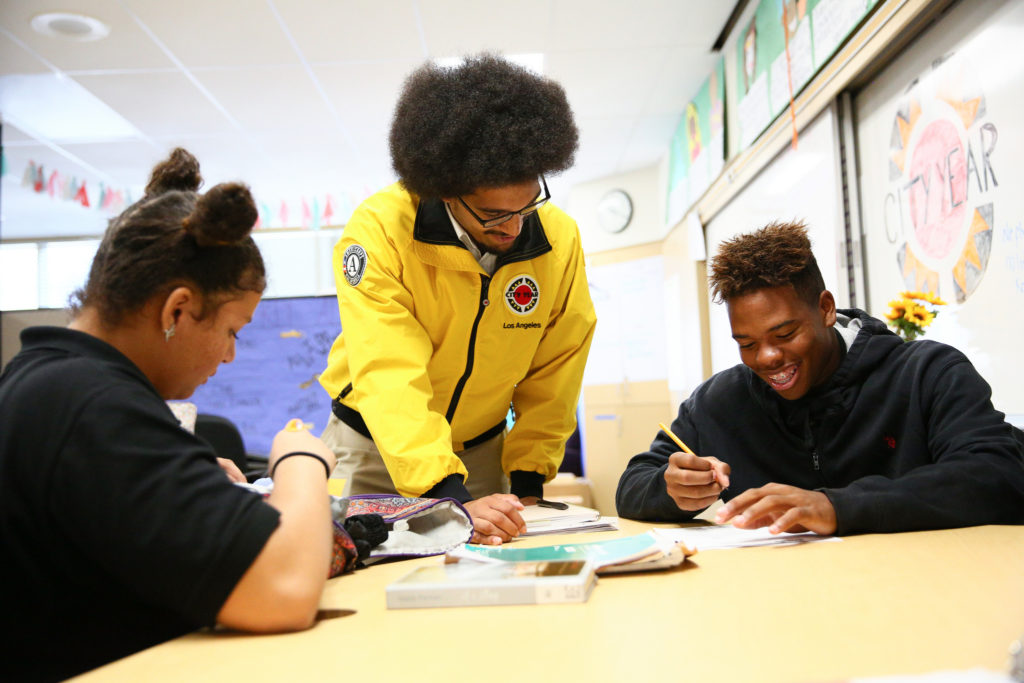

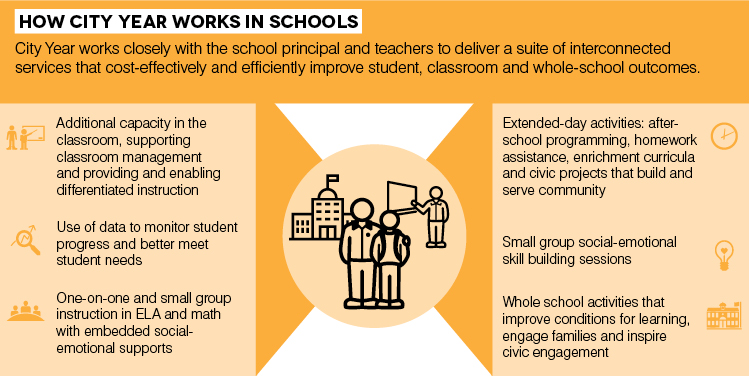

During their service year, City Year members work full time tutoring and mentoring in schools that don’t have access to resources that other schools and districts might have. They work one-on-one with elementary, middle, and high school students to provide academic and emotional support. City Year members are part of AmeriCorps, a network of national service programs addressing critical community needs.

“Where City Year AmeriCorps members step in is sitting down with students and identifying what their barrier is to attending school. Once students begin to have relationships with an AmeriCorps member, their attendance goes way up. When someone expects them to be there and is looking forward to them being there, it makes a difference,” says Erin Ross, City Year Los Angeles’ senior managing director of External Affairs.

“We’re a double bottom line program,” Ross says. “Members are doing service, but they’re also going through their service developing as leaders. We’re giving them professional skills and we’re focused on what we call ‘Leadership after City Year.’ It’s their own development, and they leave the program better prepared for whatever career they want to pursue.”

The Los Angeles office was established in 2007 and serves 31 schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District and Inglewood. For their year of service, members receive a living stipend and an educational award — up to $6,095 if they complete the required number of hours — to pay back school loans or fund future higher education. Members can receive the education award twice (for two years of service), and Ross says there’s now a network of colleges, universities, and graduate schools that match the award or supplement the funding.

That’s what drew City Year Los Angeles alum Gabriel Lopez, 31, to the organization. Lopez grew up in Chino, California and graduated from the University of California, Riverside with a Bachelor of Science degree in biological sciences in 2010, during the recession. He saw a flyer for City Year Los Angeles in the university’s science library.

“My goal was to become a doctor, but I also needed to be able to teach. Not having experience of a true 9-to-5 job or teaching, I felt this was a good combination. And to be able to do it in a community close-by that I felt like I’m a part of, even though I didn’t grow up there, was helpful,” he says.

Lopez’s first City Year Los Angeles assignment was at Robert Louis Stevenson Middle School in LA, a 35-minute drive from where he was raised.

“I didn’t come from means, but I didn’t come from an area that had particular stressors and community factors like gang violence or more extreme poverty. I worked with students who came from houses with mixed residency status. Learning to navigate all of that better informed my interventions in the day-to-day,” Lopez says.

Lopez calls his time at Stevenson Middle School his first “real” job. He signed up for a second year and became a senior corps member at Felicitas & Gonzalo Mendez High School, helping to develop the first-year corps members, who were in the position he was in just a year before.

In addition to learning to teach, he says he also developed other transferable skills. Once petrified of public speaking, Lopez served as emcee for a City Year event. He learned project management and community engagement through creating and organizing “March Mathness,” a sports-themed math fair timed to coincide with the yearly NCAA college basketball tournament. And he learned leadership.

“[At first,] I didn’t think I’d be able to lead my team during March Mathness and draw out passion and buy-in from the community to make it a really awesome event,” Lopez says. He eventually convinced local businesses to make donations towards the creation of interactive booths — a baseball activity taught multiplication; a basketball station taught integers and positive and negative values; a football booth taught fractions.

After his two years at City Year, Lopez enrolled in the PRIME-Leadership and Advocacy Program at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and concurrently earned a master’s degree at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He now works in Massachusetts for Boston Medical Center and the East Boston Neighborhood Center.

As part of a research project for Harvard’s school of public health, he says he utilized his people skills, teaching, and community engagement to analyze data and produce a report that helped inform public policy about how to manage the Zika virus in the U.S.

Ross says a significant number of the City Year Los Angeles alumni pursue careers in medicine, although the overwhelming majority become teachers. And because Los Angeles Unified School District is experiencing a teacher shortage, it now has a formal pathway that enables AmeriCorps members to complete two years in the program and coursework to become a Los Angeles Unified School District teacher. The pathway also covers the costs of the credentialing.

As for results, Ross says a year-over-year analysis shows that students assigned to work with City Year Los Angeles members attend school an average of six days more than their peers. Since schools are funded based on average daily pupil attendance, City Year Los Angeles estimates it has saved the Los Angeles Unified School District more than $1 million in six years.

“No matter what you go on to do professionally, spending a year in a systematically under-resourced community, working alongside a diverse team, overcoming adversity, all of that prepares you” [to enter the workforce], says Ross.

Lopez agrees. He says his time at City Year gave him the “audacity to pursue my dreams.”

“Every day I live and reap the benefits of what I learned. I owe a lot to the experiences I had,” Lopez says. “People are starting to know, ‘Oh, you did AmeriCorps? What was your year of service?’ You start talking about it, and during interviews, I beam with pride with what my students and my team have done. It’s obvious you get a lot out of it and I think I’m where I am in large part because of the community I joined when I was part of City Year.”

City Year is now accepting new applications through Nov. 15.