In today’s employment climate there’s an abundance of stories about the increasing importance of lifelong learning when it comes to the future of work. However, there’s another critical aspect of learning that is long overdue for attention — experiential learning. It’s the personal learning a person accumulates over their lifetime, and traditionally it’s been ignored by academics and employers.

As the job market swells, employers are beginning to feel the pinch for talent possessing the skills necessary for today’s jobs. So they’re looking to schools and non-traditional educational pathways to fill that gap, quickly and effectively. The best way to do this is to tap into the more than 31 million unserved adult learners in the U.S., assess what they already know and fill in the knowledge gaps via fast-tracked degrees, certifications, or credentials.

See Also: Opportunity awaits lifelong learners in the Fourth Industrial Revolution

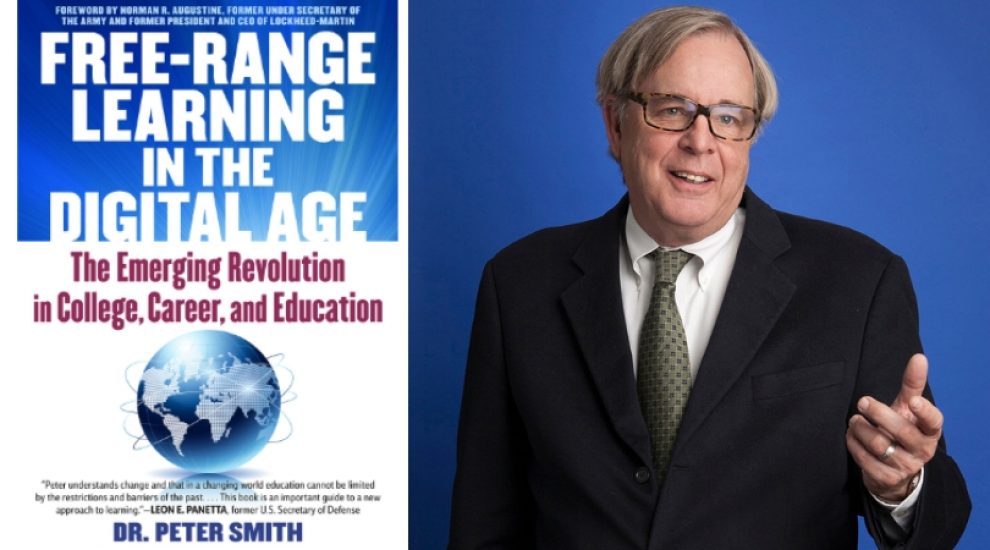

Dr. Peter Smith has devoted the better part of his life (over 45 years) to helping adult learners assess their knowledge and get the personalized education they need to accomplish their professional goals.

Smith created and served as the founding president of the Community College of Vermont (CCV) in 1970. The college was designed around the radical concept of accessing adults prior experiential learning for academic credit to give them a head start on the path to a college degree. As Assistant Director-General for Education at UNESCO, Smith helped “globalize” open educational resources, making access to high-quality content free and simple around the world. Today, Smith is The Orkland Endowed Chair and Professor of Innovative Practices in Higher Education at the University of Maryland University College (UMUC) and sits on Open Education Consortium’s board of directors.

His latest book, Free-Range Learning in the Digital Age: The Emerging Revolution in College, Career, and Education, is a resource on how adults can assess their prior learning, learn to take ownership of their skill sets and enhance them through alternative educational pathways.

One thing you should take away from this book is that adult learners have not been forgotten. The idea of a one-size-fits-all approach to education is being turned on its head. There are people out there working hard to develop and deliver “adult-friendly” educational opportunities for those who want to futureproof themselves in the new technological world of work. It’s their innovation and the compelling stories of some of the people they’ve impacted that offer hope for a thriving future economy. This book has the potential to be life-changing for millions of people and should be added to everyone’s personal library.

Below is my interview via email with Smith about his book.

1. You are passionate about the importance of determining your hidden credentials, or knowledge, and its impact on a person’s personal, academic and professional life. What is something someone could do tomorrow to start that process?

The critical thing to remember at the beginning is that we “forget” most of what we have learned informally or away from school. (And actually, much of what we learned in school as well.) By that, I mean we absorb the learning and, although we are using it all the time, we forget the actual consequences of our learning projects that caused the learning. What people who do prior learning assessment report, almost universally, is that the process of going back and “remembering” their personal learning is very, very powerful; indeed life-changing, for them. As one woman told me, “Now I know I’m a learner, and I’ve been a learner all of my life. I know I’ll never stop learning!” Several readers have told me the stories in the book were powerful motivators and reminders that encouraged them to engage in a reskilling or new learning activity.

As I write in the book, there are several informal exercises you can do to begin the “remembering” process. They include taking several coins out of your pocket and writing down the years they were issued. Then take each year and begin to record the major events in your life that year and think about their significance to you — socially, civically, and/or economically. There are several other ways to re-capture significant learning events and moments when “personal” learning occurred or was required to move forward.

On a more formal basis, you could reach out to any of the institutions presented in the book as “adult-friendly.” They all have websites and are “.edu.” Although each does business a little differently, all assess and recognize “prior learning,” including experiential learning. Beyond that, contacting the CAEL website and looking for a member institution near you is an option. Often, we are more comfortable with a local or near-by institution that assesses experiential learning. You can also find a complete listing in Appendix A of my book.

Online programs which assess prior learning are not numerous. Purdue Global University has a useful online option for assessing personal learning and hidden credentials. When I last looked, they had a self-paced as well as an instructor-led option. Also, they had a very cool short exercise (like 5-10 minutes) which helps you decide whether your hidden credentials are sufficiently developed to justify doing an assessment.

Two critical questions to ask when you are considering an institution are:

1. Do they accept prior learning credit?

2. Do they apply it to the degree program you are considering?

Many colleges and universities accept prior learning credit but do not count it towards majors and minors or general education requirements. So, while it goes on your transcript, it does not count towards the degree. Unless you’ve changed majors or you want to major in something brand new, this constitutes “knowledge discrimination” and you should choose an institution that respects your learning.

2. What’s the first thing someone who is looking to reskill, upskill, or change careers should do to find the right alternative pathway for them?

At this point, there is no “centralized” hub for getting the best information tailored to your situation for reskilling or career change. In the book, I discuss several options for this. Although the list is not comprehensive, those listed, such as

- the US Army’s “COOL” site, which translates military experience and training into civilian job qualifications, or

- the ACE credentialling center which evaluates thousands of corporate and other professional development courses for academic equivalence are current, reliable examples of ways to assign academic or employment value to learning done away from higher education.

Using them is a way to get a rough idea of what your hidden credentials might be worth in the academic world.

There are also several businesses and non-profits I discuss in my book and list in the Appendix that do a terrific job of connecting people and their interests with good content and job information. They include Credly, Portfolium, Degreed, eMSI, and Burning Glass Technologies. Each is different, and each is changing and developing rapidly. However, they share a “learner-centered” focus and are worth looking into to see if there is a good “fit” with the individual who is looking for options.

3. As technology changes the delivery of education, what effect will that have on employment at learning institutions and the role of the faculty there?

At the very least, faculty and other roles will change and evolve in the vast majority of existing institutions as they adapt to the changing context within which they operate. In the newly established institutions and programs encouraged by the Emerging Revolution driven by technology enhancement, the professional educational roles will be different by design and appropriate to achieving the goals and objectives of those programs.

There are some hard facts here. First, technology makes the delivery of educational services less expensive while increasing the quality of the content and learner experience. So, there is a significant increase in the opportunity to serve people who have heretofore been unserved and to do so with higher quality and lower costs. And the effectiveness of these services will be higher and more “learner-friendly.”

Second, the college and university world does not control the drivers of the changes that are coming. For the first time, the emerging technological capacity is developing dramatically different possibilities for learning and work. At the same time, because colleges and universities do not control the “drivers” of this disruptive change, they will face competing opportunities for learning and work preparation that was unthinkable 15 years ago. This is a textbook example of the disruptive change that Clayton Christiansen first described in his book on disruptive theory twenty years ago.

Many people argue that there will be fewer faculty and jobs because of these developments. I disagree. I think there will be different and quite possibly more professional jobs in the learning space. However, those jobs will be different, and they will include learning/curricular design, innovative and high-quality assessment services crossing education and work, and support services that give the learner/worker the information and guidance they need on an as-needed basis. Also, the role of Artificial Intelligence in helping learners construct more accurate and effective academic and employment paths will skyrocket.

What scares some university and college employees is that the traditional faculty functions, such as curriculum development, control of the curriculum, and evaluation of learning, as well as faculty governance, will change significantly. Faculty will become partners in the educational process, but they will not control it as they have historically. And, correspondingly, other professional support functions in the traditional model of higher education will change as well.

4. Of the five college presidents you spoke with for the book, there was a consensus of the importance of colleges aligning with the workplace to ensure success. How do you see colleges competing with the new digital platforms to develop a pipeline of talent for today’s workforce?

There will be several types of relationships between colleges and the new digital platforms you describe. First, some colleges will try to “go it alone.” They will not succeed or compete well in this emerging environment. Why? Because the change in the development and refinement of these new platforms is too rapid and sophisticated, hence expensive, for colleges to compete with. This is a critical point. The drivers for most of the technologically-enhanced changes that are impacting the higher education/workforce space are not controlled by the higher education communities affected. So, they are not only separately financed but also independent of institutional control. So, for almost the first time, higher education will not control the progress, development, and evolution of these new services.

The second category of relationships will involve multiple types of collaboration and partnership between and among institutions, employers, businesses and agencies to serve the needs of people trying to assemble an education/employment pathway initially and then repeatedly throughout their lives. These collaborations will take many forms.

However, I believe that they will include several common elements and characteristics:

1. Common definitions of knowledge, skills, and abilities so that a person’s knowledge and experience can be applied to either academic requirements or employ, met requirements.

2. Shared assessments of learner/employee need to fine-tune and improve the alignment of those needs with each other, thus saving time, money, and frustration.

3. Including the “human” or soft skills often associated with the Liberal Arts in the overall package of knowledge, skills, and abilities are essential “job-holding” and career flexibility skills.

5. There are some pretty exciting ideas for future educational and career preparedness opportunities and access to those opportunities, what are you most excited about?

As I write in Free-Range Learning in the Digital Age: The Emerging Revolution in College, Career, and Education, I am most excited about the opportunity to recognize the staggering amount of human potential, talent, and capacity that is walking around in America. As the interviews narrate, the personal learning that people do—the learning that happens throughout life and outside of formal schooling—is deep and profound. Yet we have had a practice of what I call “knowledge discrimination” in higher education and employment which says that where you learn is more important than how well you know it and can apply it.

Furthermore, our traditions have encouraged the belief that failure in school or failure to go to higher education is your (the individual’s) fault. So, we are penalizing people who, for good reason, may have missed the boat the first time around with self-guilt. Moreover, we penalize them again when they try to convert their personal learning to a job or academic value, and we tell them “no.” This leads to what Norman Augustine called the “parchment ceiling” in his Introduction to the book.

The stories in the book — excerpts of interviews with college presidents, adult learners, workers, and innovators — make the human case for the impact of these practices in ways that data never could. They underscore the life-changing effect of having your personal learning recognized and valued. Meanwhile, they show the cost of wasting all this latent talent that is walking around our country, unrecognized. It is destructive to the individual and harmful to the broader community and the social fabric of the country, as well as our tax base.

The technological enhancements and innovations are the tools with which we can scale educational and employment opportunity in a way that was inconceivable 15 years ago. However, it’s the payoff, the consequences of this dramatically increased opportunity, resulting in more confident, more respected, and more economically secure lives is what excites me the most.

You can read more on this topic at Smith’s blog, www.rethinkinghighereducation.net, and via his previous books, Harnessing America’s Wasted Talent: A New Ecology of Learning (2010), The Quiet Crisis: How Higher Education is Failing America (2004) and Your Hidden Credentials: The Value of Learning Outside of College (1986).

Join the Conversation: What do you think the future of education looks like for adult learners? Tell us your ideas on our Facebook page.