The increasing trend of jobs requiring a four-year degree is disenfranchising millions of working-age Americans and costing companies money, according to a new report from the Harvard Business School.

It is called “degree inflation” and it is happening in jobs and career tracks which, in previous decades, a worker did not need a Bachelor’s degree to gain entry. And for a growing amount of middle-skill job openings, it is an automatic disqualification if a job-seeker does not tick off this box on an online application.

“Dismissed by Degrees” co-author and Harvard Business School Professor of Management Practice Joseph Fuller compared this phenomenon to a virus spreading through the workforce and damaging the overall competitive health of the United States’ labor market.

“As [employers] upcredential a job, it raises the skill requirement further and more of the workforce gets frozen out of what is traditionally a well-paying middle-skill job,” Fuller said.

With 6.8 million unemployed Americans and another 6.7 who are underemployed and looking for full-time work, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, increasing barriers to employment is restricting growth. Taken with a record 6.1 million job openings as of this past July, “it is further proof that the jobs market is working inefficiently,” the report said.

The disconnecting of an ample supply of working-age adults has been attributed to globalization, automation and aging, but the report brings attention to a solvable problem: companies should assess what competencies a job needs instead of relying on a college degree requirement as a proxy for these skills.

The report – co-authored by HBS’ Project on U.S. Competitiveness & Project on Managing the Future of Work Program Director Manjari Raman and published with Accenture and Grads of Life – combines research into 26 million job postings and a survey of 600 business and human resource leaders into a compelling narrative which crosses socioeconomic and demographic barriers and delivers a message to employers: overhaul degree requirements and rediscover underused workforces or risk being left behind.

By identifying the problem of degree inflation, Fuller and Raman reveal the fundamental imbalances affecting the U.S. labor economy and the growing gap in middle-skills jobs employment, which comprise a “sizeable proportion of U.S. private sector employment.” It also reveals that employers are ignoring or unaware of the total costs of hiring and retaining workers with four-year degrees.

Fuller said that the report is targeting business leaders to get them to rethink their hiring strategies and to challenge misperceptions of college graduates and less-educated but experienced workers. According to Fuller, employers are succumbing to degree inflation because they believe they are sourcing a workforce with both hard and soft skills and that traditional sources of non-degree talent were lacking both. Employers also reported that it was easier to hire college graduates due to an oversupply in the market following the Great Recession.

RELATED STORY: Joe Biden wants to strengthen the middle class with workforce training

This strategy is working against them by shrinking an already tight labor pool even further. The unemployment rate for college graduates was 2.7 percent in 2016 leading the report’s authors to ask the logical question, “Why would companies choose to make those middle-skills positions even harder to fill by requiring a college degree?”

Fuller said that employers are not looking at the big picture. “They only understand one side of the ledger. They look at what they do today as having zero incremental costs and they look at making an investment in developing a talent pipeline for anything other than the highest-skilled jobs as an added cost.”

The survey data show that employers are paying a premium for these workers compared to non-degree workers with experience. For example, construction, educational services and information technology companies pay 21 percent to 31 percent more for recent college graduates and manufacturers and retailers pay 11 percent to 20 percent more.

“55 percent of the companies we talked to acknowledged that they pay more college workers for the exact same job. Almost 70 percent say they pay 11 to 30 percent more. That’s a lot of money,” Fuller said.

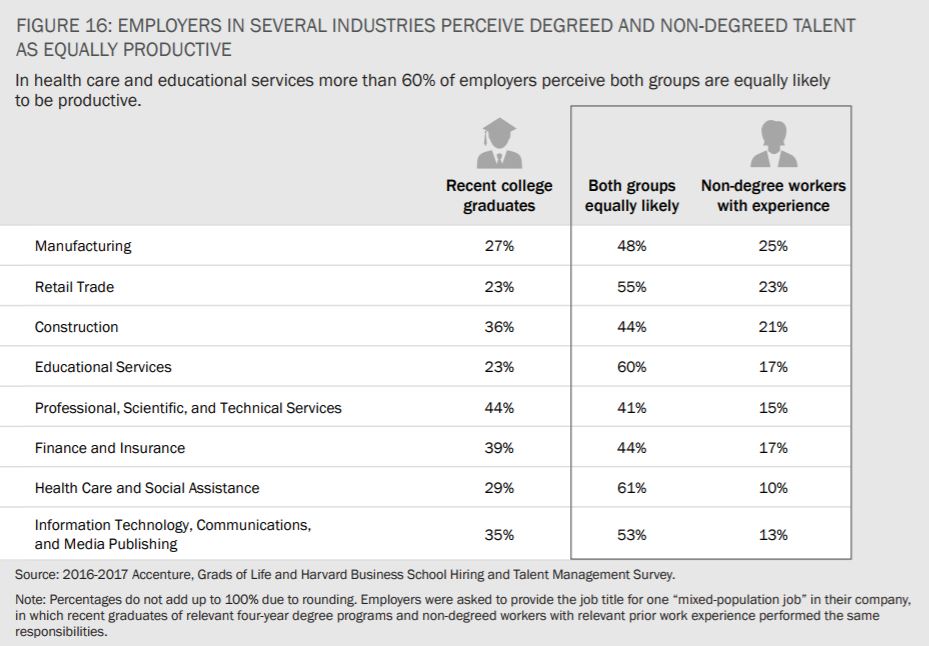

Yet 49 percent of the employers surveyed viewed workers in these “mixed population jobs” – meaning the same jobs are done by recent college graduates and non-degree workers with experience – as equally productive.

“You’re paying someone 20 percent more for a $50,000-a-year job. That’s ten grand. That’s even before you get to the indirect costs,” Fuller said. “If the cost of [employers] lazily defaulting to requiring college degrees is $20,000 a year, what if they pocketed $10,000 and spent the other $10,000 on training somebody? That’s a hell of a return on investment.”

By ignoring talented non-degree workers, companies are also being hurt by longer job fulfillment periods and higher turnover from college graduates. The higher turnover rate is connected to survey respondents’ belief that college graduates were “more likely to feel unengaged or underutilized compared with non-degree workers.”

Fuller thinks that companies can increase their growth by understanding the economics and logic behind their hiring processes. Doing the math, Fuller said, and utilizing the data available from human resource departments could force companies to look at their bottom line and see how their standards are holding them back.

The report cites strategies some companies are taking to address the problem of sourcing talented workers. Walmart is looking to train its incumbent workforce to climb the management career ladder through its Walmart Academies. Swiss Post is engaging younger workers with its renowned Leadership Academy. And JP Morgan Chase & Co. is investing in middle-skill workers by strengthening workforce development programs and career-focused education in underserved communities.

RELATED STORY: To combat the employment crisis, JP Morgan Chase expands its successful mentorship program

“Smarter companies will start making choices like the ones we are suggesting and they will gain a competitive advantage and perform better. If [competitors] see the performance of JP Morgan Chase going up because they have more multilingual tellers and customer service representatives than their competition, these competitors are losing their market share and will figure out why,” said Fuller.

Toy manufacturer Hasbro and Rhode Island healthcare company Lifespan have partnered with Year Up, a non-profit organization training low-income young adults. They are tapping into an underutilized workforce dubbed “Opportunity Youth” which is comprised of nearly six million young people aged 16-24 who are not in school and are not working. This and other public-private partnerships are a win-win for companies and for their local communities, according to Fuller.

“We know that there are models and pathway programs like Year Up that have succeeded in helping Opportunity Youth overcome barriers and build competencies to be workforce-ready,” Fuller said. “For employers, it allows them to be more active and effective citizens. Also, there is a significant uplift in incumbent employee engagement and motivation because they see the company working to address visible social issues locally.”

It is Fuller’s hope that companies take the initiative in creating the next generation of middle-skills workers by eliminating outdated concepts of today’s workers and match them with training programs, via apprenticeships or career technical education, to ensure they have the competencies for the changing workforce. They also can be instrumental in creating a systemic shift in the education system, by sharing relevant job data so educators can align their curricula to meet 21st-century standards and workforce demands.

“What we want as an employer or educator is that we need to start thinking about competencies, not academic credentials. If we taught people who will never go to college the ways to read data, to gather data and the 10 basic principles of statistics, they will be much more job-ready than sitting through a year of Algebra II.”

To read the entire report, “Dismissed by Degrees: How degree inflation is undermining U.S. competitiveness and hurting America’s middle class,” click here.

Join the Conversation: What do you think about the report’s conclusion that degree inflation is sidelining millions of capable workers? Tell us your thoughts on our Facebook page.