At a time when the U.S. labor market favors workers seeking new opportunities, many older women appear stuck. The ability to advance one’s career and earnings is an important personal and public policy goal without a pre-determined “shelf life.”

When experienced women have fair opportunities to grow their skills, talents and pay, their own bottom lines are strengthened, and so are productivity and economic growth. Policymakers can do more to support women’s economic advancement and demographic trends underscore the urgency of doing so.

In recent decades, older women have become a large and growing share of the labor force. Today, more than one in ten workers is a woman over the age of 55 and the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that by 2031, their ranks will expand by an additional 2.2 million. Last month, the labor force participation rate for women aged 55 to 64 reached 61% – nearly the highest level ever recorded.

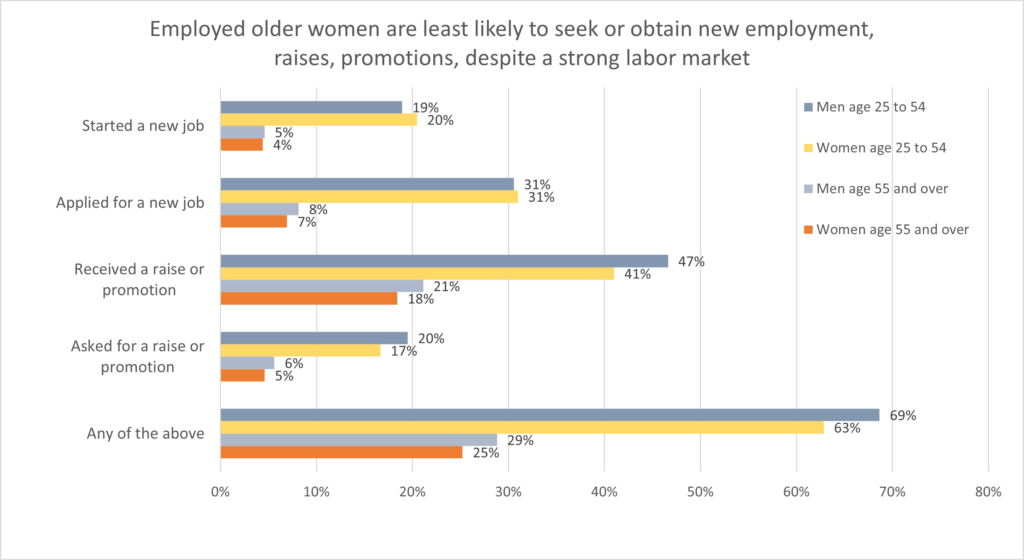

What is more, workers looking to enhance their earnings have historic opportunities to do so, thanks to the strength of the U.S. labor market. As employers compete to fill vacancies, workers are finding they can move up by acquiring new skills, promotions and raises, or move on to new job opportunities. But new and troubling data suggest that few older women are moving up or moving on, despite their labor market participation gains.

Analysis of the 2022 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking finds that fewer than one in four women aged 55 and over asked for a raise, received a raise, applied for a job, or started a new job in the prior year. By comparison, 28.8% of men aged 55 and over and large majorities of those aged 25 to 54 – 62.9% of women and 68.7% of men – had sought out or achieved raises, promotions, or new jobs.

But before leaping to the conclusion that older women simply need to get better at “leaning in,” we should recognize the structural obstacles that can get in their way.

First, older women experience occupational segregation to an even greater extent than other women, meaning they tend to be clustered in occupations marked by lower-than-average pay and prospects for advancement. As a result, one of the tried-and-true paths to growing one’s earnings – seeking out new job opportunities – is a less reliable strategy for large numbers of older women.

Second, age discrimination, though illegal, remains pervasive and has an outsized impact on women. Age discrimination undermines career mobility when older women are unfairly denied opportunities to move up through promotions, training, or advancement.

Age discrimination can also undermine women’s efforts to move up by moving on to new jobs. AARP polling found that half of older workers with household incomes under $50,000 reported that they felt unable to change jobs because of their age and polling from NORC and AP (Associated Press) found that eight in ten older women believe their age is a disadvantage when it comes to finding work.

Third, older individuals appear to have less access to employer-provided job training than their younger peers, even though they place just as high a priority on training opportunities. Older adults are also less likely to obtain training from the federal-state workforce system. Without access to training, avenues to advancement can be closed off.

Finally, the disproportionate caregiving responsibilities older women carry, even past the childbearing years, can create obstacles to career mobility. Older women are five times more likely than their same-aged, male peers to have caregiving impact their employment. Family responsibilities may mean women are not in an equal position to pursue promotion, upskilling, or reskilling, without additional supports.

These obstacles are not simple to dismantle, but progress is urgently needed for reasons of equity and economic growth in the face of demographic trends.

Strengthening and clarifying protections against age discrimination is an obvious first step. Recent court decisions have muddied the waters around the applicability of anti-discrimination protections for job applicants, as well as raised the burden of proof individuals must meet to prove unlawful age bias. Proposed legislation in the form of the Protecting Older Job Applicants Act and the bipartisan Protecting Older Workers Against Discrimination Act would help put victims of age discrimination on fairer footing to challenge unfair treatment.

Policymakers can also take steps to center older women in workforce policy. For example, skills-based hiring initiatives at all levels of government can be especially helpful for older women, who are less likely to hold college degrees than other workers. In addition, reauthorization of the Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act (WIOA) gives stakeholders an opportunity to make the workforce system more age-inclusive, by defining and centering the needs of older women workers through targeted training, job search, and wrap-around services that directly address barriers facing them.

WIOA reauthorization can also allow for a re-examination of performance standards for federally funded job training to ensure they appropriately account for age discrimination and other structural barriers facing older workers in becoming re-employed.

Finally, Congress can do more to shore up the Senior Community Service Employment Program (SCSEP), both through annual appropriations and future Older Americans Act reauthorization. As the only federal job-training program focusing exclusively on the needs of vulnerable older workers (two-thirds of whom are women), SCSEP’s reach has shrunk, even as the need for its services has grown.

Economic inclusion means we all should be able to pursue goals of career advancement without fear of an arbitrary expiration date. Policymakers have ready opportunities to support inclusion by strengthening protections against age discrimination and modernizing the workforce training system to meet the needs of older women. As the ranks of older women in the workforce grow, the time is ripe to act.

Beth Almeida is a senior fellow with the Center for American Progress. Her research focuses on women’s economic security, aging and retirement, and the labor market.